After years of nascent fiddling and stop-and-start organizing, the Cincinnati transit and urbanism movements have started to gel in substantial ways. Come September 2016 the city will have a modern streetcar system running through its downtown to prove the movement’s combined worth.

This is a city, remember, that is infamous for its woes with rail transit, none more striking than its abandoned subway system currently lying underneath city streets. It’s also a Midwest city fighting for urban relevancy at a time where cities like Chicago and Minneapolis gobble up all the good Midwest millennial talent, places like Atlanta and Dallas continue to invest in their urban cores with miles of rail, and global cities like Sydney expect to see huge growth along to-be-constructed light rail lines.

But the days where Cincinnati trails its transit peers is over, says local leaders and grassroots advocates who can now boast that the city has reversed decades of population decline and is showing significant strides in becoming a creative class hotspot. And now with the 3.6 mile streetcar project, seen as an economic development tool just as much as a transit project (within a few blocks of the route an estimated $300-500 million in spinoff investment has recently occurred), 2016 promises to put an exclamation point on recent wins.

The story that has brought these movements together started way back in 2001 after a sweeping regional rail service initiative was soundly defeated by a 2:1 margin. Not dismayed, local transit advocates saw a silver lining in the polling results that showed immense popularity for rail transit in the downtown area. So they decided on a new approach to bring rail back to Cincinnati, one with a laser focus on the city core.

According to John Schneider, one of the local urbanists responsible for the streetcar coming to fruition, it was during this time that Ohio Senator Mark Mallory showed a keen interest in rail transit. “He called me up and asked to learn more about light rail and streetcars, and we met at the Graeters on Reading Road for a long talk.”

It was that talk that paved the way for the streetcars coming to Cincinnati. Fortuitously, Mallory went on to become Mayor in 2005 and one of the eventual political adversaries to move the streetcar conversation forward.

Thereafter, the Cincinnati Business Committee invested $50,000 in a credible study outlining a route and its projected benefits and costs. “This was all advocate-led, bringing leaders to the table and trying to keep them there,” says Schneider. “That’s really unusual for one of these projects.”

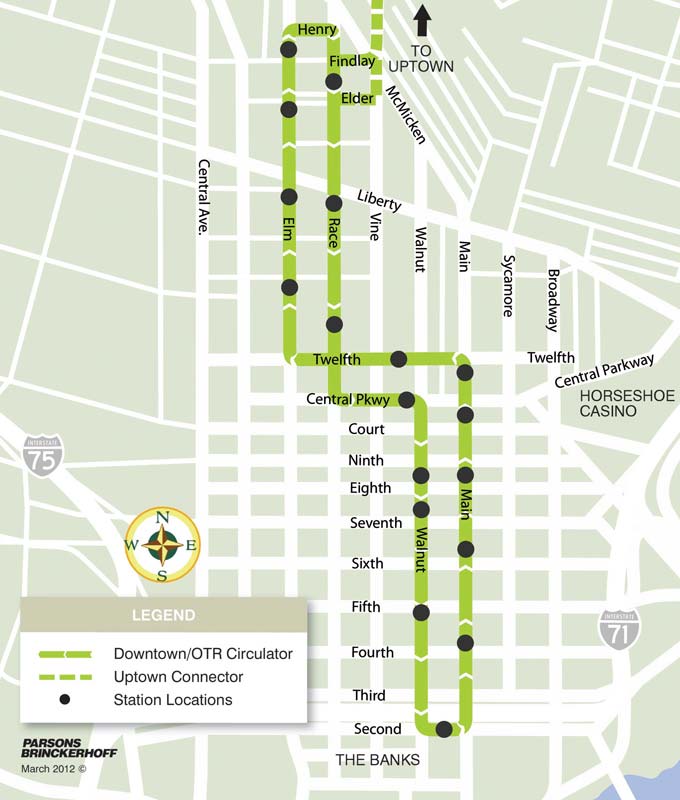

By 2007, the feasibility study had been completed and the proposal for a rail loop through the city core was hardened. That route was later broadened to include an extension to the Uptown area to capture more jobs and University students as well as grow political support for a still soft project.

But before advocates and the Mayor could gain too much in the way of progress, in 2009 and again in 2011 the anti-tax group COAST lobbed ballot initiatives to stop the project dead in its tracks.

The referendums would have amended the City Charter to require a vote on all future expenditures on any passenger rail project. Both were eventually defeated by a majority of Cincinnati voters. Widely seen as a referendum on the streetcar itself, the initiative’s defeat was a major victory for Schneider and transit advocates in the city, and for Cincinnati Mayor Mark Mallory.

Those wins were short lived, however, and in 2011 advocates again faced another rail enemy with the newly elected Governor John Kasich who took away $52 million in state money that had been awarded to the streetcar by the previous administration.

The 3.6 mile streetcar route that is now built, connecting downtown with the Over-the-Rhine neighbourhood.

The City was forced to postpone the Uptown connection and moved forward with a slightly shortened downtown route. By the end of 2012 construction had started and nearly a ½ mile of rail been laid on the project.

It was at this time that the project faced its most serious setback when Mayor-elect Cranley and a newly elected, anti-rail City Council voted 5 to 4 to suspend work on the project and bring in an independent auditor to analyze the cost of completion versus the cost of cancellation.

While all of this happened, an army of supporters and volunteers collected signatures for a ballot measure on behalf of the streetcar. While it never came to a vote, the Council vote set off a maelstrom of grass-roots activity, organized under the moniker Believe in Cincinnati, to save the streetcar.

“There were a lot of people who realized, once the audit came back, that the numbers were just unacceptable,” said Eric Avner in an interview with the New York Times in 2013, vice president of the Haile foundation. “Cincinnati did not have the luxury of wasting that much money.”

Local grassroots group Believe in Cincinnati quickly organised and helped keep the streetcar project moving forward.

With a ballot measure pressure mounting and the results of the audit, it was enough to produce a veto-proof 6-to-3 Council vote to resume construction and eventually finish the project.

Yvette Simpson, a council member who voted for the project, summed up her support to the New York Times in 2013: “It’s not just about a streetcar. It’s that Cincinnati can accomplish great things.”

With such ardent grassroots urbanism and transit movements now working simultaneously, it should come as no surprise, then, that even greater things are in store for the city. “The Cincinnati Streetcar is a new choice that we hope will lead to a more balanced transportation system,” explains Schneider. “Advocates are hoping that seeing the streetcars operating -- actually light rail vehicles -- will re-start the light rail conversation again.”